Selfless Souls

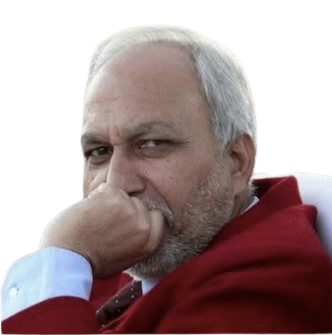

'Wildlife Man' Mohammad Ahsan, IFS (Retd. Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, UP, in conversation with HN Singh

Q: You have had an illustrious career in the Indian Forest Service. Could you walk us through your journey from your early postings to eventually becoming the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests?

I joined the Indian Forest Service in 1978. There was a two-year training-cum-probation at IGNFA (then Indian Forest College), Dehradun, followed by four months at LBSNAA, Mussoorie. Thereafter, it was almost a smooth journey via Almora, Kalagarh (as SDO, Project Tiger, Ramnagar), and Gorakhpur as WPO, then Pilibhit as DFO. In 1986, I was posted as Director, Kanpur Zoo, not knowing then that the job would last five years. But I thoroughly enjoyed it, more as a hobby than a job. In 1991, I was elevated to the rank of Conservator of Forests (CF) and posted as CF, Shiwalik Circle, Dehradun, for two years. This was followed by postings as Director, Rajaji National Park, and then a continuous four years as CF, Yamuna Circle. These four years offered me unique and unforgettable exposure to forest working in the high hills, now part of Uttarakhand. My tenure in Corbett as Field Director was short (1999–2000) but rich in experience and professionally very satisfying. In the same year, after the state of Uttar Pradesh was bifurcated, I was posted in Lucknow as CF (Wildlife). This posting, which lasted about three years, was significant as it exposed me to the workings of many lesser-known Wildlife Sanctuaries, including several bird sanctuaries. Later, I served as Chief Wildlife Warden, UP, for more than three and a half years. It was a responsibility so big that it often made me nervous, perplexed, and tense — yet it offered immense exposure not only to the complexities of wildlife management but also to the work culture of state and central governments, and legal proceedings in higher courts, including the Supreme Court, which I had to attend frequently in connection with wildlife cases. Then came a year-long stint as MD (Managing Director), UP Forest Development Corporation — a tenure I frankly do not wish to remember. I discovered that I had no temperament for cutting and selling timber lots. This was followed by more than three years as APCCF (Social Forestry), and finally, a brief tenure as PCCF, UP. Throughout, I was labelled a "wildlife man" because of my multiple postings in wildlife areas and perhaps also due to my natural inclination toward wildlife matters.

Q: During your tenure, what were some of the major challenges you faced in the field, and how did you overcome them?

There are numerous challenges, both personal and professional, that a forest officer typically faces. On a personal front, the lack of basic educational and healthcare facilities at smaller, remote postings in the early years is a real issue. Professionally, the challenges are area-specific, although forest fires, poaching, and illegal felling are universal. These are worsened when the officer is understaffed, has inadequately trained or ill-equipped personnel, and lacks access to technology-based tools. While posted in the high hills, I often regretted not being able to inspect all areas due to distance, inaccessibility, and difficult terrain. Ironically, finding the means and time to inspect our areas was itself a challenge. Rajaji National Park posed another issue: it had a highly fragmented habitat. The challenge here was to provide corridors for wild elephants, who, in the absence of connectivity, were confined to isolated forest pockets, escalating man-animal conflict. Another significant hurdle was utilizing budget allocations from centrally sponsored schemes. These often arrived at the very end, sometimes on the last day of the financial year. Meanwhile, fieldwork went on throughout the year, often on credit. This issue was particularly severe in the wildlife sector. As MD, UPFC, the biggest challenge was to keep the Corporation financially viable. Timber production was declining, yet the Corporation was viewed by government and employees alike as a "milch cow". As APCCF, Social Forestry, the challenge lay in coordinating with multiple departments, sourcing funds, identifying plantation sites, and meeting politically mandated targets of planting crores of saplings and ensuring their survival. In short, every position came with its own set of challenges.

Q: You are known to have taken some solid and impactful decisions during your service. Could you share a few that you feel made a lasting difference to forest management or conservation efforts?

A few initiatives during my tenure as CWLW, UP, stand out. Chief among them was the establishment of the Sarus Protection Society, followed by the Tiger Protection Society, both supported by substantial government grants. The Lion Safari Project in Etawah and the Bear Rescue Centre in Agra also took shape during my tenure. Joint Forest Management saw significant growth and government support, both central and state, during my time as APCCF, Social Forestry. However, I believe it still has a long way to go to become a fully democratic institution.

Q: In your experience, how important is on-ground fieldwork and grassroots engagement in the success of forest and wildlife conservation policies?

Truly speaking, the frontline staff is the backbone of forest and wildlife conservation. However noble or well-planned our policies may be, their success depends entirely on implementation in the field and that lies in the hands of frontline workers. They work in often harsh and adverse conditions. The credit for any success must go to them.

Q: What role do you think today's youth and citizen volunteers can play in protecting forests and biodiversity?

Article 51A(g) of the Indian Constitution mandates that every citizen has a fundamental duty to "protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers, and wildlife, and to have compassion for living creatures." This entrusts citizens with an active role in conservation. But much also depends on the school system and curriculum. Environmental education may be mandatory in most schools and colleges, but it’s up to the teachers to instill constitutional values and environmental ethics in students.

Q: If you were to look back, what values or principles guided you throughout your service as a forest officer?

A senior officer I deeply admired once remarked, "Three-fourths of our problems are self-created." He was referring to greed, lies, and dishonesty, the honey traps of life. I’ve tried to steer clear of those. Integrity, humility, and respecting others' dignity have been cardinal principles for me in both public and private life. Listening to others with empathy has also helped immensely.

Q: Many people retire and step away, but you seem to remain deeply connected with nature and environmental causes even today.

My bond with forests is both emotional and spiritual. I never viewed trees merely as sources of timber or firewood. To me, forests are sacred, a source of inner peace and spiritual cleansing. Life hasn’t changed much after retirement, except that I no longer go to the office. Even during service, I was a reader in three languages, a book collector, a poet, a writer, a photographer, a cactus grower, and a driftwood collector, though I never publicized these pursuits. Post-retirement, I’ve simply continued these passions; the only difference is that now, people know about them.

Q: Could you tell us about the work you continue to do personally?

I enjoy giving lectures on forests and the environment, leading nature walks, and speaking about trees, birds, bees, and butterflies. I also enjoy talking about the history of heritage buildings and photographing them.

Q: After such a decorated service career, what inspired you to take up mobile photography?

In my youth, I dreamt of photographing beautiful buildings and landscapes, but struggled with heavy manual cameras. I deferred the dream. With the arrival of the iPhone 3 in the late 2000s, I discovered that mobile phones could help me realize my long-held dream. I began photographing heritage structures, leafless trees, clouds, flowers, insects, and more, eventually expanding into street photography. And I’ve never looked back.

Q: Your mobile photography, especially of dew drops, rain-soaked leaves, and forest textures, has drawn attention. How do you see it contributing to awareness about nature?

I love photographing nature, though I know mobile phones have limitations, especially for wildlife or bird photography. So, I focus on aspects of nature that respond well to mobile photography, like butterflies, insects, dewdrops, flowers, autumn scenes, and forest textures. Recently, I’ve ventured into street photography too.

Leave a comment