Expert Expressions

Dr CP Rajendran is an adjunct professor at the National Institute of Advanced Sciences, Bengaluru, and co-author of the book: The Rumbling Earth – The Story of Indian Earthquakes

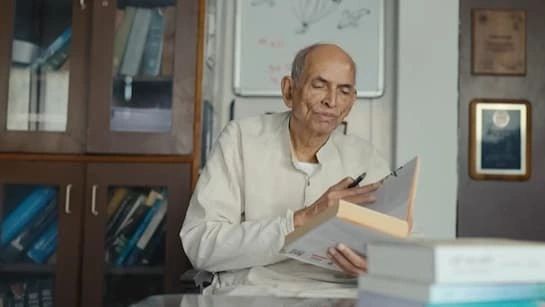

Professor Madhav Gadgil, who passed away on January 7, is universally acknowledged as the foundational figure who shaped modern ecological and environmental studies in India.

He joined the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) as a faculty member in the early 1980s, following his doctoral studies in mathematical ecology at Harvard University. Shortly thereafter, in 1983, he founded the Centre for Ecological Sciences, which he nurtured into a premier institution for ecological research.

While at IISc, I was reminded of Madhav Gadgil by a tree-like, gigantic climber in an ecological park near my old research office. The association felt profoundly apt, for Gadgil, who had planted that remarkable specimen, was himself a phenomenal, foundational figure in Indian environmental science: a sturdy, wide-canopied climber-tree whose work provided shade and structure for an entire field of study.

Gadgil’s 2023 autobiography, A Walk Up the Hill: Living with People and Nature, reveals how his early life forged his unique philosophy. More than a memoir, it presents a vision for uniting ethics, science and practical life. He emphasises that his ecology is rooted not only in laboratories but in humility, justice and care for both nature and people.

The narrative makes clear that his worldview was shaped by a profound closeness to nature, meaningful associations with people across diverse socio-economic realities, and a sharp awareness of the injustices they endured. Childhood wanderings—birdwatching, trekking, and observing forests—taught him to see nature as a living, locally integrated entity. These formative experiences were later enriched and affirmed through his associations with naturalists like Salim Ali and environmentalists like Sundarlal Bahuguna, further strengthening his resolve to bridge ecological science with social equity.

An experience from his youth, around the age of 12, may have laid a crucial foundation for this vision. He recounts a trek in 1954 in Yavateshwara, near his mother’s home, a small scenic village nestled in the hills about four kilometres west of Satara city, close to the Western Ghats: “I went there for a trek with our gardener’s young son. Not having carried any water, we were thirsty after a 3-hour trek in the hot sun. At last, we had reached the lonely temple on the hilltop. It had a large Gular tree, and in the shade was a well and next to it the priest’s house. When we requested him for water, he curtly asked: ‘Are you Brahmins? I have water only for other Brahmins.’ It was then that I vividly realised why both Baba and my mother, Pramila, said that caste was an abomination. I replied that we were not Brahmins and we walked on.”

His father, Dhananjay Ramchandra Gadgil, a renowned economist, brought him up in a non-religious environment, and Madhav himself did not wear the sacred thread. This early, visceral encounter with caste-based exclusion became a defining moment, embedding in him a deep awareness of social injustice that would later inform his ecological philosophy—one that inherently linked the well-being of people with the well-being of the land.

His scholarship uniquely wove rigorous Western scientific training with a deep respect for Indian traditional knowledge, cultivating a distinctly Indian school of ecological thought that was both globally informed and locally rooted. He inspired and trained a vast majority of India’s leading ecologists today, creating a ‘family tree’ of scientific thought that continues to grow. His own research spanned a breathtaking range, from theoretical ecology and evolutionary biology to applied studies on riverine ecosystems, forest management and human-wildlife conflict. He made seminal contributions to understanding patterns of species diversity and resource partitioning.

His public engagement matched Gadgil’s immense erudition. He published seminal research while also writing extensively on the critical interrelationship between environment and society, propagating his ideas with the heart of an activist. In recent years, he conducted significant research and outreach in collaboration with his late wife, the renowned meteorologist Sulochana Gadgil.

He published many excellent research papers. Not only did he have immense erudition in ecology, but he also wrote about the interrelationship between environment and society and propagated his ideas with the heart of an activist. His intellectual legacy is embedded in national policy; the 2002 Biological Diversity Act and the 2006 Forest Rights Act, passed by the Government of India in 2003, bear his influential imprint.

His legacy embodies a paradox familiar to great visionaries— the seminal 2011 Gadgil Committee Report on the Western Ghats, which is both his most celebrated and most contentious work. Though it stands as a landmark document for India’s environmental movement, its recommendations faced political reluctance. The report remains a classic, prescient blueprint for conserving one of the world’s most critical biodiversity hotspots. It underscored the painful but essential conflict between long-term ecological security and short-term economic interests. The ongoing environmental crises in the Western Ghats stand as a stark validation of his warnings.

Scientists are generally known to be ivory tower residents who avoid any connection with the outside world. Madhav Gadgil was an irreplaceable great scientist who had an active exchange of ideas with society. For Gadgil, ecology was not a remote science. It was intrinsically linked to social justice, equity and democratic participation of local communities in managing their natural resources. In essence, Madhav Gadgil taught India to see its environment not just as a repository of resources, but as a complex, living system intertwined with culture and survival. He gave Indian ecology its voice, its scientific backbone and its moral compass. Remembering him is a call to revisit his core principle: that true development must be ecologically sensitive and inclusive, listening to both scientific evidence and the wisdom of the people who inhabit the land.

Remembering Professor Madhav Gadgil is to celebrate not just an individual, but an entire philosophy of science that is democratic, rigorous and rooted in the Indian context.

Leave a comment