Your Right To Info

TreeTake Network

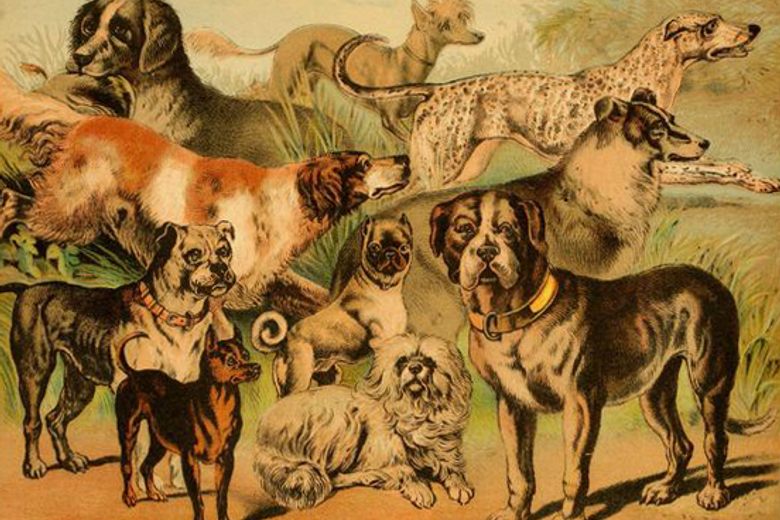

Would you believe a shih tzu shares a common ancestor with an Irish wolfhound? With over 400 recognized breeds, the number of dog varieties is enough to spin one’s head. But as per genetic studies, all dogs trace their origin to an extinct wolf species, the canis lupus. It is fascinating to trace the evolution of dogs from a bulky wolf to toy species like shih tzu and chihuahua.

Selective breeding has occurred for thousands of years in numerous domesticated species, not just dogs. In dogs, breeding for specific behavioural traits took place occurred first. However, where and when certain types of dogs originated is still uncertain. When researchers compared the genetics of several well-known breeds of herding dogs, they found that one group of dogs had its origins in the United Kingdom, another from Northern Europe, and yet another group from Southern Europe. Looking closer, they found each group used a different strategy to herd their flocks. This supports the growing theory that multiple human populations started the purposeful breeding of dogs independent of one another.

Most dog breeds of today were developed in the last 150 years, spurred by what’s known as the Victorian Explosion. During this time in Great Britain, dog breeding intensified and expanded, resulting in many recognizable breeds of dogs. The Victorians, influenced by the ideas of Darwin, became passionate about breeding for the ideal of a certain breed. Many of the conformational traits thought of as classic for a certain type of dog, have their origins in this era. Pictures of dog breeds from 100 years ago compared to their current counterparts today show the dramatic changes that have occurred as dog fanciers selectively bred for traits such as shorter legs (dachshunds were taller back then), and stockier build (German shepherd dogs were lankier at the turn of the last century). Breeding for conformational traits continued through the 20th century, the end result being the 400+ types of dogs recognized as distinct breeds.

The flip side of this extensive breeding programme was the loss of genetic diversity and conformation changes that had detrimental breed-specific health consequences, including the development of undesirable diseases. In the third decade of the 21st century, technological advances gave scientists a new perspective on dogs. At present, dogs are prone to some of the same diseases that ail humans, such as cancer, heart disease and obesity. Researchers hope that further studies might shed light on how these conditions develop and may lead to treatments. For instance, the Morris Animal Foundation Golden Retriever Lifetime Study, which is gathering lifestyle and genetic information on more than 3,000 golden retrievers, may give new information to help identify risk factors for canine diseases.

Most researchers, however, agree that dogs are really domesticated wolves as their scientific name is canis lupus familiaris. A large body of research suggests that dogs were domesticated between 12,500 and 15,000 years ago, but recent genetic studies suggest that domestication might have taken place even earlier. Some researchers believe dogs might have comingled with humans as early as 130,000 years ago, long before our human ancestors settled into agricultural communities. Another controversy surrounds the origins of these earliest domesticated dogs. Evidence pointed to both Asia and Europe as the site of initial domestication, resulting in an unusual scientific tug of war. A 2016 study suggested that dogs were actually domesticated twice –in both Europe and Asia, but a study published in 2017 pushed back these results and suggested one domestication. However, it provided evidence that this event took place earlier, between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago.

A recently published research in Cell Reports, looking at the genetics of more than 150 different dog breeds, has unearthed genetic traces of a “New World Dog” that migrated with humans across the Bering Strait. Archaeological evidence existed of this ancient dog, but the study was the first to show “living evidence of these dogs in modern breeds,” including the Peruvian hairless dog and the Xoloitzcuintle. Most other dogs in North America are of European descent, first brought to the continent by waves of soldiers and settlers, and later imported for breeding purposes. According to a study by an international team of scientists, the world's first known dog, a large and toothy canine, lived 31,700 years ago and subsisted on a diet of horse, musk ox and reindeer. If this is to be believed, the date for the earliest dog would go back by 17,700 years, since the second oldest known dog, found in Russia, dates to 14,000 years ago.

Remains for the older prehistoric dog, excavated at Goyet Cave in Belgium, suggest that the Aurignacian people of Europe from the Upper Paleolithic period first domesticated dogs. "In shape, the Paleolithic dogs most resemble the Siberian husky, but in size, however, they were somewhat larger, probably comparable to large shepherd dogs," added Germonpré, a paleontologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. For the study, the scientists analyzed 117 skulls of recent and fossil large members of the Canidae family, which includes dogs, wolves and foxes. Skeletal analysis revealed that the Paleolithic dogs had wider and shorter snouts and relatively wider brain cases than fossil and recent wolves. The skulls were somewhat smaller than those of wolves.

Isotopic analysis of the animals' bones found that the earliest dogs consumed horse, musk ox and reindeer, but not fish or seafood. Since the Aurignacians are believed to have hunted big game and fished at different times of the year, the researchers think the dogs might have enjoyed meaty handouts during certain seasons. Some experts believe dog domestication might have begun when the prehistoric hunters killed a female wolf and then brought home her pups. They also believe that the dogs were used for tracking, hunting, and transport of game. Ancient, 26,000-year-old footprints made by a child and a dog at Chauvet Cave, France indicate the dogs might have been kept as pets.

However, some experts are not convinced that the Aurignacians domesticated dogs. They feel the dogs may have undergone "self-domestication" from wolves more than once over history, which could explain why the animals appear and then seemingly disappear from the archaeological record. Experts also feel that dogs were just a loose category of wolves until around 15,000 years ago, when humans tamed them, fed and bred them. Even as wolf descendants died out, dogs grew into a new species. Humans bred hunting dogs, herding dogs, sled dogs, and guard dogs. Dogs were bred for vigilance, aggression, obedience, and companionship. But in this process, the canines were ruined. They got legs so short they could not run, noses so flat they could not breathe, tempers so hostile they could not function in society. So, man’s best intentions backfired. In defying nature, each bad gene was concentrated in a breed, magnifying its damage: epilepsy for springer spaniels, diabetes for Samoyeds and bone cancer for Rottweilers. And then, it is said that a dog is man’s best friend. True. But, can the same be said about his ‘creator’- the man!

Leave a comment