Readying for a daunting future?

India is home to 13 of 20 cities most vulnerable to environmental hazards worldwide: Report

Arunima Sen Gupta

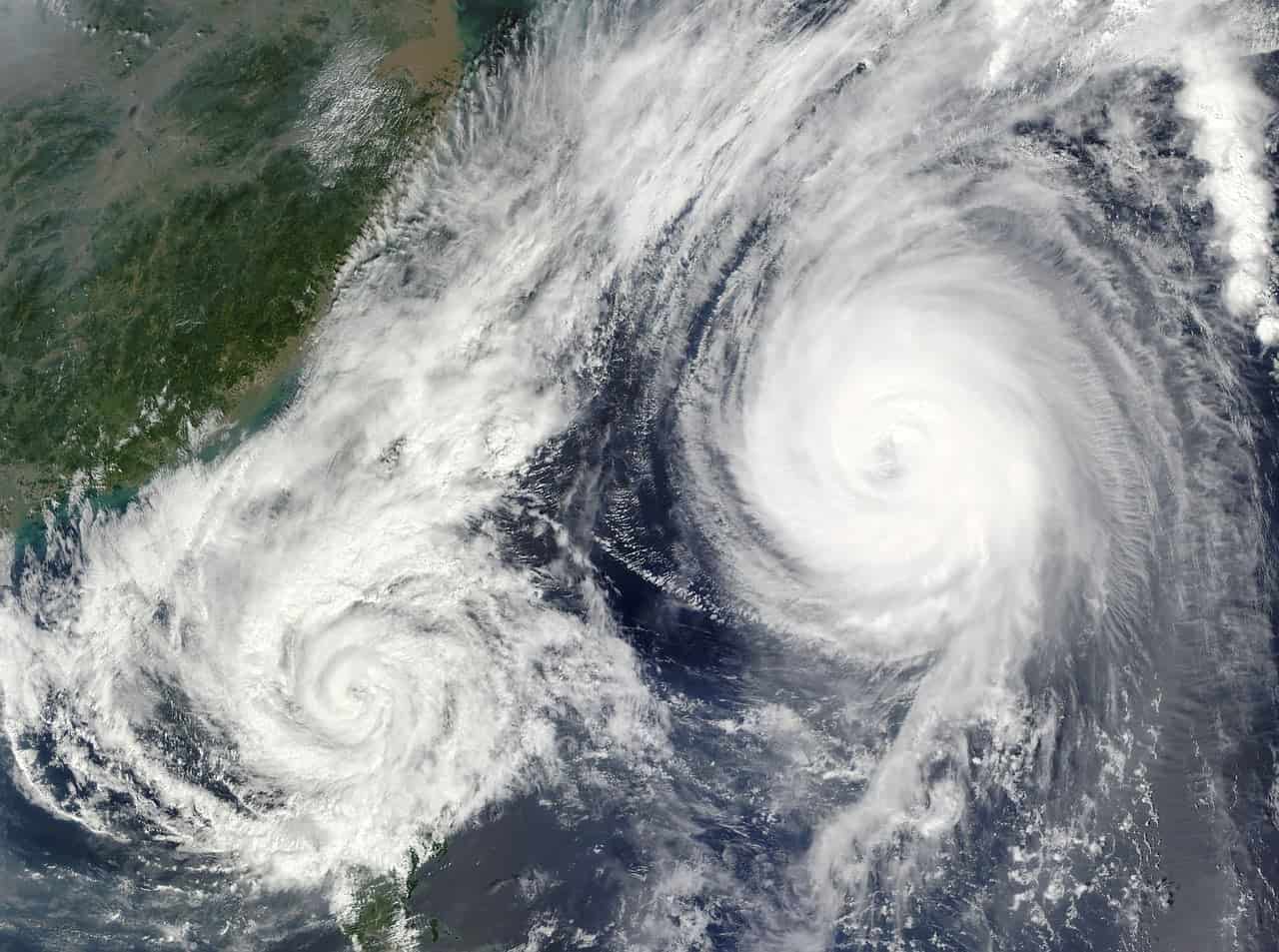

Of the 100 cities worldwide most vulnerable to environmental hazards all but one are in Asia, and four-fifths are in India or China, says a risk assessment published recently. Across the globe, more than 400 large cities with a total population of 1.5 billion are at high or extreme risk due to some mixture of life-shortening pollution, dwindling water supplies, deadly heatwaves, natural disasters and climate change, the report finds. The sinking megacity of Jakarta — plagued by pollution, flooding and heatwaves, with worse to come — topped the ranking.

But India, home to 13 of the world's 20 most risk-laden cities, may face the most daunting future of any country in the world. India's weaker governance, coupled with the size and scale of its informal economy, makes it far harder to address environmental and climate issues at the city level, the report’s lead author Will Nichols says. Delhi ranks second on the global index of 576 cities compiled by business risk analysts Verisk Maplecroft, followed within India by Chennai (3rd), Agra (6th), Kanpur (10th), Jaipur (22nd) and Lucknow (24th). Mumbai and its 12.5 million souls is 27th. Looking only at air pollution — which causes more than seven million premature deaths worldwide each year, including a million in India alone — the 20 cities with the worst air quality in the world among urban areas of at least a million people are all in India. Delhi is in pole position. The air pollution assessment was weighted towards the impact of microscopic, health-wrecking particles known as PM2.5, cast off in large measure by the burning of coal and other fossil fuels.

The impacts of climate change have never been clearer or more threatening. For India, climate change is already an existential threat. Coupled with mismanagement of resources and governance, India faces acute repercussions of climate impacts year-round in the form of extreme and unseasonal rainfall, droughts, floods and heatwaves leading to economic and livelihood losses, food and water security threats. India’s own positioning on climate change issues at global platforms appears impressive. The country faces challenges in the strategic transformation of the power sector. Coal contributes around three-fifths of India’s carbon emissions. India is still the third largest carbon emitter globally and its power sector is still highly fossilised with around 196 GW of total 347 GW installed power generation capacity by coal and lignite. During the financial year 2017-18, the country generated around 1228 billion-kWh units (BU) of electricity of which 1044 BU (around 85%) was through burning 540 million tonnes of coal and lignite, as per a Central Electricity Authority (CEA) report. The entry of new electric vehicles, clean electric cooking and proliferation of new electrical and electronic equipment is bound to give the Indian thermal power sector a rebound-effect increase. India’s quest for 450 GW addition of renewables can decarbonise the Indian power sector but will not be an easy task due to massive intermittence and identification for subsequent peak loads. Diffusion of renewable programme therefore requires proper guidance and restructuring. The existing position of renewable programme is also not very satisfactory. India has committed to generating 175 GW which is divided into 100 GW solar, 60 GW wind and 15 GW through other resources towards renewable integration by the year 2022.

The solar element which forms the largest segment and political interest is sub-divided further into two segments, with 60 GW for utility scale and 40 GW for solar rooftops. While the progress on the utility scale solar, wind and other RE components is steady with 36 GW of installation realised by July 2019, the customer centric decentralised and grid-connected solar rooftop projects have gained least traction. The 40 GW solar rooftop (SRT) programme, mainly focusing on domestic households, agriculture sector and commercial establishments, is running much behind its targets with poor adoption rates and an added cumulative capacity of just 4.5 GW. Moreover, India’s industrial and domestic energy consumption structures have challenges in energy intensity and resource utilisation inefficiency.

Every time an industrial entity produces aluminium, steel or any other consumer-oriented product without a strict adherence to recycling and/or emphasis on cleaner fuels for manufacturing process, it adds towards more fossilised economy pathways. An approach towards circular economy with emphasis on resource substitution, efficient and minimal resources utilisation, and thrust towards reusing and recycling can help in addressing climate change goals. This can not only decarbonise the economy but also reduce the challenges of environmental degradation and pollution. Further, the energy and energy efficiency programmes cannot function optimally when they are only focused on technical and economic potential without addressing the behavioural patterns of actual target audience.

With India’s growing energy demand, energy planning has to be strategically thought within the limits of new technology paradigms, material criticality and human behavioural changes. Such programmes must not only be perceived from an investment-drive perspective but also from a necessity point of view. Mass mobilisation is central to tackle an enormous and encompassing challenge of climate change. In this regard, the role of youth is critical. For India, addressing climate change no longer remains a matter of choice. It is a question of survival of its communities in millions that face unseasonal rainfall, prolonged droughts and agricultural shortfalls. However, what is required is an integrated, ambitious and urgent approach which requires three-tier changes at policy and institutional level; industrial and applied segments; and consumer level behavioral interventions with community and citizen participation. Transition of course will not be simple and without sacrifices. Nevertheless, science provides basic foundations to design new pathways to address the energy transitions and coping with climate change through technological innovations.

China's middle class

Outside Asia, the Middle East and North Africa have the largest proportion of high risk cities across all threat categories combined, but Lima is the only non-Asian city to crack the top 100. “Home to more than half the world's population and a key driver of wealth, cities are already coming under serious strain from dire air quality, water scarcity and natural hazards,” the report’s lead author Will Nichols says. “In many Asian countries these hubs are going to become less hospitable as population pressures grow and climate change amplifies threats from pollution and extreme weather, threatening their role as wealth generators for national economies.” While richer than India, China faces formidable environmental challenges as well.

Thirty-five of the 50 cities worldwide most beset by water pollution are in China, as are all but two of the top 15 facing water stress, according to the report. But different political systems and levels of development may ultimately play in China’s favour, Nichols adds. “For China, an emerging middle class is increasingly demanding cleaner air and water, which is being reflected in government targets,” he says. “China's top-down governance structure and willingness to take abrupt measures, such as shutting down factories to meet emissions goals gives it more of a chance of mitigating these risks.”

Africa hit hardest

When it comes to global warming and its impacts, the focus shifts sharply to sub-Saharan Africa, home to 40 of the 45 most climate-vulnerable cities on the planet. The continent least responsible for rising global temperatures will get hit the hardest not only because of worse droughts, heat waves, storms and flooding, but also because it is so ill-equipped to cope. “Africa's two most populous cities, Lagos and Kinshasa, are among those at highest risk,” the report notes. Other especially vulnerable cities include Monrovia, Brazzaville, Freetown, Kigali, Abidjan and Mombasa. The climate index combined the threat of extreme events, human vulnerability, and the ability of countries to adapt.

The first in a series of risk assessments for cities, the report evaluates threats to liveability, investment potential, real estate assets, and operational capacity.

Leave a comment